A digital signal processor (DSP) is a specialized microprocessor with an optimized architecture for the fast operational needs of digital signal processing.[1][2]

Contents[hide]

|

[edit] Typical characteristics

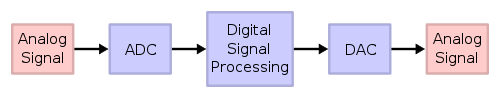

Digital signal processing algorithms typically require a large number of mathematical operations to be performed quickly and repetitively on a set of data. Signals (perhaps from audio or video sensors) are constantly converted from analog to digital, manipulated digitally, and then converted again to analog form, as diagrammed below. Many DSP applications have constraints on latency; that is, for the system to work, the DSP operation must be completed within some fixed time, and deferred (or batch) processing is not viable.

Most general-purpose microprocessors and operating systems can execute DSP algorithms successfully. But these microprocessors are not suitable for application of mobile telephone and pocket PDA systems etc. because of power supply and space limits. A specialized digital signal processor, however, will tend to provide a lower-cost solution, with better performance, lower latency, and no requirements for specialized cooling or large batteries.

The architecture of a digital signal processor is optimized specifically for digital signal processing work. Most also support some of the features as an applications processor or microcontroller, since signal processing is rarely the only task of a system. Some useful features for optimizing DSP algorithms are outlined below.

[edit] Architecture

By the standards of general purpose processors, DSP instruction sets are often highly irregular. One implication for software architecture is that hand optimized assembly is commonly packaged into libraries for re-use, instead of relying on unusually advanced compiler technologies to handle essential algorithms.

Hardware features visible through DSP instruction sets commonly include:

- Hardware modulo addressing, allowing circular buffers to be implemented without having to constantly test for wrapping.

- A memory architecture designed for streaming data, using DMA extensively and expecting code to be written to know about cache hierarchies and the associated delays.

- Driving multiple arithmetic units may require memory architectures to support several accesses per instruction cycle

- Separate program and data memories (Harvard architecture)

- Special SIMD (single instruction, multiple data) operations

- Some processors use VLIW techniques so each instruction drives multiple arithmetic units in parallel

- Special arithmetic operations, such as fast multiply-accumulates (MACs). Many fundamental DSP algorithms, such as FIR filters or the Fast Fourier transform (FFT) depend heavily on multiply-accumulate performance.

- Bit-reversed addressing, a special addressing mode useful for calculating FFTs

- Special loop controls, such as architectural support for executing a few instruction words in a very tight loop without overhead for instruction fetches or exit testing

- Deliberate exclusion of a memory management unit. DSPs frequently use multi-tasking operating systems, but have no support for virtual memory or memory protection. Operating systems that use virtual memory require more time for context switching among processes, which increases latency.

[edit] Program flow

- Floating-point unit integrated directly into the datapath

- Pipelined architecture

- Highly parallel multiplier–accumulators (MAC units)

- Hardware-controlled looping, to reduce or eliminate the overhead required for looping operations

[edit] Memory architecture

- DSPs often use special memory architectures that are able to fetch multiple data and/or instructions at the same time:

- Harvard architecture

- Modified von Neumann architecture

- Use of direct memory access

- Memory-address calculation unit

[edit] Data operations

- Saturation arithmetic, in which operations that produce overflows will accumulate at the maximum (or minimum) values that the register can hold rather than wrapping around (maximum+1 doesn't overflow to minimum as in many general-purpose CPUs, instead it stays at maximum). Sometimes various sticky bits operation modes are available.

- Fixed-point arithmetic is often used to speed up arithmetic processing

- Single-cycle operations to increase the benefits of pipelining

[edit] Instruction sets

- Multiply-accumulate (MAC, aka fused multiply-add, FMA) operations, which are used extensively in all kinds of matrix operations, such as convolution for filtering, dot product, or even polynomial evaluation (see Horner scheme)

- Instructions to increase parallelism: SIMD, VLIW, superscalar architecture

- Specialized instructions for modulo addressing in ring buffers and bit-reversed addressing mode for FFT cross-referencing

- Digital signal processors sometimes use time-stationary encoding to simplify hardware and increase coding efficiency.

[edit] History

Prior to the advent of stand-alone DSP chips discussed below, most DSP applications were implemented using bit slice processors. The AMD2901 bit slice chip with its family of components was a very popular choice. There were reference designs from AMD, but very often the specifics of a particular design were application specific. These bit slice architecture would sometimes include a peripheral multiplier chip. Examples of these multipliers were a series from TRW including the TRW1008 and TRW1010, some of which included an accumulator, providing the requisite multiply-accumulate (MAC) function.

In 1978, Intel released the 2920 as an "analog signal processor". It had an on-chip ADC/DAC with an internal signal processor, but it didn't have a hardware multiplier and was not successful in the market. In 1979, AMI released the S2811. It was designed as a microprocessor peripheral, and it had to be initialized by the host. The S2811 was likewise not successful in the market.

In 1980 the first stand-alone, complete DSPs – the NEC µPD7720 and AT&T DSP1 – were presented at the International Solid-State Circuits Conference '80. Both processors were inspired by the research in PSTN telecommunications.

The Altamira DX-1 was another early DSP, utilizing quad integer pipelines with delayed branches and branch prediction.

The first DSP produced by Texas Instruments (TI), the TMS32010 presented in 1983, proved to be an even bigger success. It was based on the Harvard architecture, and so had separate instruction and data memory. It already had a special instruction set, with instructions like load-and-accumulate or multiply-and-accumulate. It could work on 16-bit numbers and needed 390ns for a multiply-add operation. TI is now the market leader in general-purpose DSPs. Another successful design was the Motorola 56000.

About five years later, the second generation of DSPs began to spread. They had 3 memories for storing two operands simultaneously and included hardware to accelerate tight loops, they also had an addressing unit capable of loop-addressing. Some of them operated on 24-bit variables and a typical model only required about 21ns for a MAC (multiply-accumulate). Members of this generation were for example the AT&T DSP16A or the Motorola DSP56001.

The main improvement in the third generation was the appearance of application-specific units and instructions in the data path, or sometimes as coprocessors. These units allowed direct hardware acceleration of very specific but complex mathematical problems, like the Fourier-transform or matrix operations. Some chips, like the Motorola MC68356, even included more than one processor core to work in parallel. Other DSPs from 1995 are the TI TMS320C541 or the TMS 320C80.

The fourth generation is best characterized by the changes in the instruction set and the instruction encoding/decoding. SIMD and MMX extensions were added, VLIW and the superscalar architecture appeared. As always, the clock-speeds have increased, a 3ns MAC now became possible.

[edit] Modern DSPs

Modern signal processors yield greater performance. This is due in part to both technological and architectural advancements like lower design rules, fast-access two-level cache, (E)DMA circuit and a wider bus system. Of course, not all DSPs provide the same speed and many kinds of signal processors exist, each one of them being better suited for a specific task, ranging in price from about US$1.50 to US$300.

A Texas Instruments C6000 series DSP clocks at 1.2 GHz and implements separate instruction and data caches as well as an 8 MiB 2nd level cache, and its I/O speed is rapid thanks to its 64 EDMA channels. The top models are capable of as many as 8000 MIPS (million instructions per second), use VLIW (very long instruction word) encoding, perform eight operations per clock-cycle and are compatible with a broad range of external peripherals and various buses (PCI/serial/etc). TMS320C6474 chips each have three such DSPs, and the newest generation C6000 chips support floating point as well as fixed point processing.

Another player at the high-end signal processor manufacturer today is Freescale. The company provides a multi-core DSPs family MSC81xx. The MSC81xx is based on StarCore Architecture processors. The latest MSC8144 DSP combines four programmable SC3400 StarCore DSP cores. Each SC3400 StarCore DSP core runs at 1 GHz. The SC3400 performed higher than any other programmable DSP at 1 GHz on BDTIsimMark2000 results published by Berkeley Design Technology, Inc. (BDTI).

Another major signal processor manufacturer today is Analog Devices. The company provides a broad range of DSPs, but its main portfolio is multimedia processors, such as codecs, filters and digital-analog converters. Its SHARC-based processors range in performance from 66 MHz/198 MFLOPS (million floating-point operations per second) to 400 MHz/2400MFLOPS. Some models even support multiple multipliers and ALUs, SIMD instructions and audio processing-specific components and peripherals. Another product of the company is the Blackfin family of embedded digital signal processors, with models like the ADSP-BF531 to ADSP-BF536. These processors combine the features of a DSP with those of a general use processor. As a result, these processors can run simple operating systems like μCLinux, velOSity and Nucleus RTOS while operating relatively efficiently on real-time data.

Another player is NXP Semiconductors based on TriMedia VLIW technology, optimized for audio and video processing. In some products the DSP core is hidden as a fixed-function block into an SoC, but NXP also provides a range of flexible single core media processors, such as the with a complete software development kit and a library of codecs and filters. The TriMedia media processors support both fixed-point arithmetic as well as floating-point arithmetic, and have specific instructions to deal with complex filters and entropy coding.

Most DSPs use fixed-point arithmetic, because in real world signal processing the additional range provided by floating point is not needed, and there is a large speed benefit and cost benefit due to reduced hardware complexity. Floating point DSPs may be invaluable in applications where a wide dynamic range is required. Product developers might also use floating point DSPs to reduce the cost and complexity of software development in exchange for more expensive hardware, since it is generally easier to implement algorithms in floating point.

Generally, DSPs are dedicated integrated circuits, however DSP functionality can also be realized using Field Programmable Gate Array chips.

Embedded general-purpose RISC processors are becoming increasingly DSP like in functionality. For example, ARM Cortex-A8 has a 128-bit wide SIMD unit that can have impressive 16- and 8-bit performance for industry standard benchmarks. OMAP3 processors include a Cortex-A8, and optionally incorporate a C6000 DSP, so designs can choose the best approach: higher end DSP, or ARM-based "DSP lite".

[edit] See also

- U.S. Robotics, Courier modems - Internal DSP design allowed soft upgrades.

- IBM Mwave - Combined modem/sound DSP card allowing soft upgrades.

- Digital Signal Controller

[edit] References

- ^ Yovits, Marshall C. (1993). Advances in computers. 37. Academic Press. pp. 105-107. http://books.google.com.sg/books?id=vL-bB7GALAwC&pg=PA105.

- ^ Liptak, Béla G. (2006). Instrument Engineers' Handbook: Process control and optimization. 2. CRC Press. pp. 11-12. http://books.google.com/books?id=TxKynbyaIAMC&pg=PA11.

[edit] External links

- DSP Processor - Core-Based Wireless System Design

- Microcontroller.com

- DSP Engineering Magazine

- Introduction to DSP - Processor tutorial

- Improv Systems Homepage

- Analog Devices Homepage

- DSP Discussion Groups

- DSP Online Book

- DSPs and VLIW

- Pocket Guide to Processors for DSP - Berkeley Design Technology, INC

- DSP Online eBooks

- Texas Instruments DSP Homepage

- CEVA, Inc. Homepage

- Freescale Semiconductor Homepage

- BDTi

- BDTI DSP Kernel Benchmarks Results

- The 2008 EDN DSP directory

- DSP-FPGA.com Magazine

- AR Parameter Estimation using TMS320C30

- TI DSP Selection Tool

No comments:

Post a Comment